In “Nature”: Galaxies out of a Supercomputer

A new computer simulation shows the formation of galaxies with unprecedented precision, allowing astrophysicists from Heidelberg, the U.S. and England to indirectly confirm the standard model of cosmology.

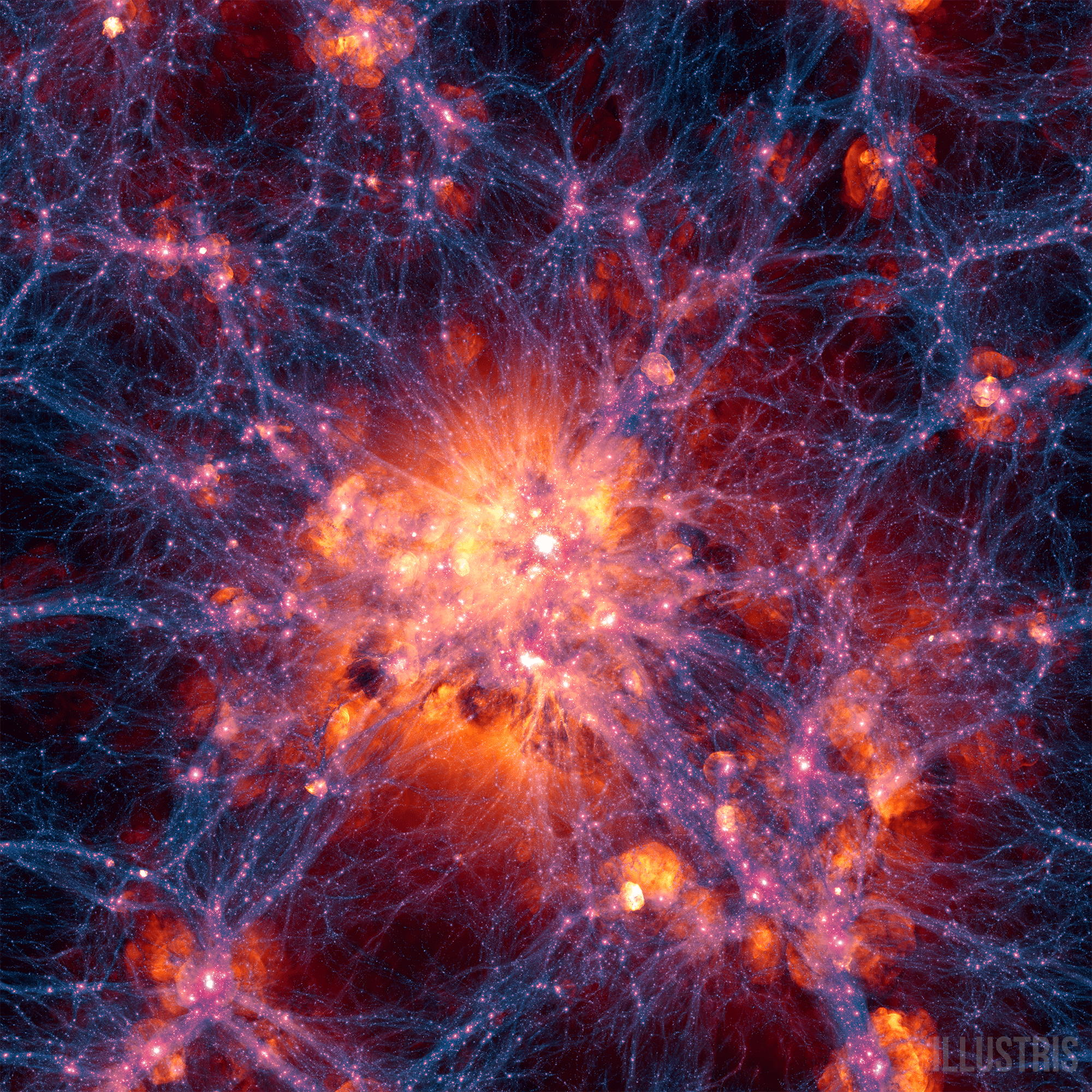

Galaxies are typically comprised of several hundred billion stars and display a variety of shapes and sizes. The formation of galaxies is one of the most involved and complex problems of astrophysics. In cooperation with an international team of scientists at the MIT, Harvard University and other institutions, scientists at the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies (HITS) have now succeeded in simulating the physics of galaxy formation in a vast region of space with very high accuracy. In the journal Nature, they report that the calculation yielded for the first time a realistic mix of elliptical and spiral galaxies. Moreover, the simulation can explain the enrichment of heavy elements (so-called “metals”) in neutral hydrogen gas. In addition, the calculated galaxies are distributed in space as observed with telescopes. The “Illustris” simulation project produced more than 200 terabyte of data and required the combined power of more than 8,000 processors for several months. The simulation was possible thanks to the AREPO code for cosmological structure formation, which was developed at HITS, and the supercomputers CURIE in France and SuperMUC in Germany. The virtual universe that the scientists created allows a variety of novel predictions as well as comprehensive tests of cosmological theories of galaxy formation.

The standard model of cosmology is based on the hypothesis that the Universe is dominated by unknown forms of matter and energy. We do not know the true physical nature of dark matter and dark energy yet, but their impact can be understood with the help of supercomputers. Previous simulations of the cosmos generated a cosmic web of matter concentrations that showed a passing resemblance to the galaxy distribution. However, they were not able to create elliptical and spiral galaxies and follow the small-scale evolution of interstellar gas and stars, which are closely linked to each other. With the ambitious “Illustris” project, the cosmologists have now taken a major step towards addressing this issue.

In the world’s largest hydrodynamic simulation of galaxy formation, 13 billion years of cosmic evolution were followed in a cube of 350 million light-years across, beginning 12 million years after the Big Bang. During this time, the “primordial soup” consisting of hydrogen, helium gas and dark matter formed increasingly big clumps, pulled together by gravity. Finally, galactic stellar systems developed, whose growth is regulated by the complex interplay between radiation processes, hydrodynamic shock waves, turbulent flows, star formation, supernova explosions and the energy supplied through growing supermassive black holes. The Illustris team was able to calculate these physical processes with the AREPO code in its new supercomputer simulation. AREPO is a “moving mesh code”, which does not partition the simulated universe with a fixed grid but rather uses a movable and deformable mesh, which allows a particularly accurate processing of the vastly different size and mass scales occurring in individual galaxies.

The main simulation of the project employed more than 18 billion particles and cells and bridges a dynamic range of more than one million per space dimension – if a photo needed to resolve similarly small details, it would have to offer one million megapixels. The memory consumption of the Illustris simulation was more than 25 terabyte, and the generated data volume of over 200 terabyte sets a new record in cosmology. This flood of data makes it possible to study the evolution of about 50,000 well-resolved galaxies in detail, and to make theoretical predictions for cosmological structure formation with high accuracy.

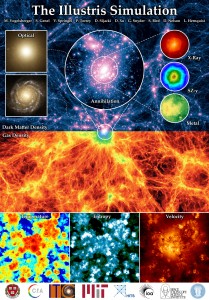

Several years of preparatory work for the simulation paid off: For the first time, the famous “tuning fork diagram” of galaxy morphology, which goes back to Edwin Hubble, can be reproduced (see figure 1). Mark Vogelsberger (MIT), first author of the initial study on Illustris, published in Nature, says: “It is remarkable that the universe’s initial conditions as observed after the Big Bang can actually produce galaxies with the right sizes and shapes.” Indirectly, the findings can be regarded as a confirmation of the standard model of cosmology. “We can finally leave the old and coarse models of galaxy formation behind and not only precisely calculate dark matter, but also the ordinary visible matter,” says Prof. Volker Springel, group leader of the HITS research group “Theoretical Astrophysics” and author of the AREPO code. He adds: “The Illustris results mark a radical change in theoretical studies of galaxy formation.” Figure 2 gives an overview of different astrophysical quantities that this “universe in a supercomputer” predicts.

Original scientific publication:

M. Vogelsberger, S. Genel, V. Springel, P. Torrey, D. Sijacki, D. Xu, G. Snyder, S. Bird, D. Nelson, L. Hernquist. “Properties of galaxies reproduced by a hydrodynamic simulation”, Nature, May 8, 2014, doi:10.1038/nature13316

Further links:

Website of the Illustris Project (with further visualizations)

Gauss Centre for Supercomputing

SuperMUC at the Leibniz Computing Center

AREPO-Code: V. Springel, 2010, MNRAS, 401, 791

Press contact:

Dr. Peter Saueressig

Head of Communications

Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies (HITS)

Phone: +49-6221-533245

Peter.saueressig@h-its.org

www.h-its.org

Twitter: @HITStudies

Scientific contact:

Prof. Dr. Volker Springel

Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies (HITS)

Tel: +49-6221-533-241

volker.springel@h-its.org

www.h-its.org

About HITS

HITS, the Heidelberg Institute for Theoretical Studies, was established in 2010 by physicist and SAP co-founder Klaus Tschira (1940-2015) and the Klaus Tschira Foundation as a private, non-profit research institute. HITS conducts basic research in the natural, mathematical, and computer sciences. Major research directions include complex simulations across scales, making sense of data, and enabling science via computational research. Application areas range from molecular biology to astrophysics. An essential characteristic of the Institute is interdisciplinarity, implemented in numerous cross-group and cross-disciplinary projects. The base funding of HITS is provided by the Klaus Tschira Foundation.